What is Digital Art?

- Gretchen Andrew

- Oct 6, 2025

- 3 min read

When we ask “what is digital art?”, we’re talking about a field with over half a century of history. Far from being a passing trend, digital art has continuously evolved, shaping how we think about technology, creativity, and visual culture.

The Early Days: Computers as Creative Partners

The term “digital art” first gained traction in the 1960s, when artists such as Harold Cohen began using computers as collaborators rather than just tools. Cohen’s plotter drawings, algorithmic compositions, and pioneering program AARON positioned the computer as a generative partner in the creation of art.

Video, Net Art, and the Politics of Code

By the 1980s and 90s, artists explored video, interactivity, and the internet. Nam June Paik used video and satellite transmissions to collapse geographical boundaries, while artists like JODI and Olia Lialina (an early mentor of my own digital practice) explored the aesthetic and political possibilities of early internet culture.

This era highlighted not just new creative forms, but also questions of interface, accessibility, and the politics of code, laying the foundation for how digital technologies would shape art and society.

Virtual Reality, Immersive Environments, and AI

The 2000s and 2010s brought an explosion of experimentation with virtual reality, immersive environments, and blockchain-based art. More recently, AI has emerged as a dominant force, with artists like Refik Anadol embracing artificial intelligence as a generative and expansive tool.

Much of this work celebrates novelty, expansion, and play—the ability of digital tools to generate the new.

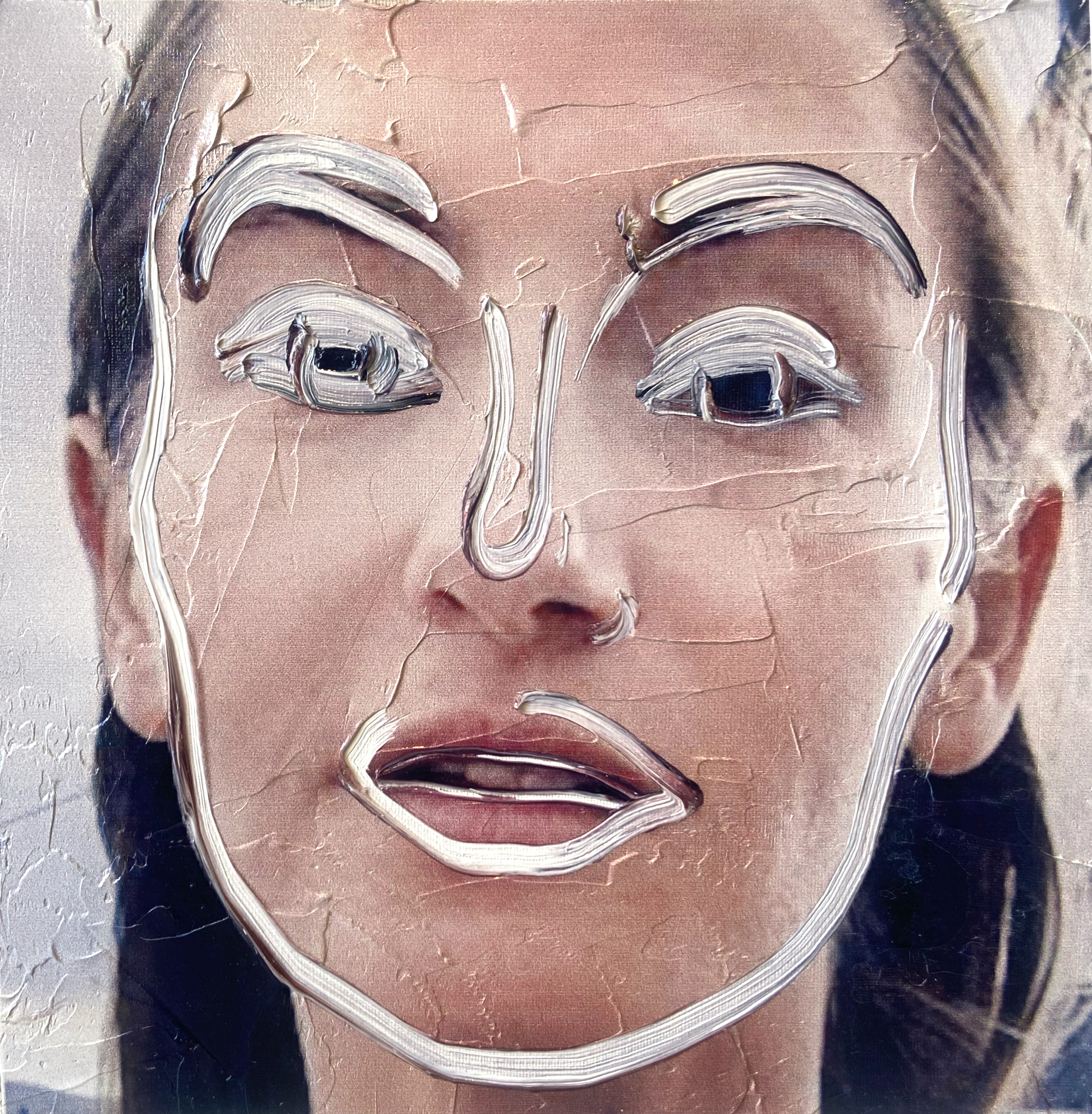

Facetune Portraits: Everyday Digital Tools as Ideology

It’s within this broader genealogy that I situate my Facetune Portraits. Unlike the exuberant generative work often celebrated today, this series engages with a much more everyday tool: Facetune.

Facetune is designed to smooth, reshape, and standardize facial features. In other words, it embodies AI not as creativity, but as homogenization. By translating this app into painting, the Facetune Portraits expose the ways AI-driven beauty standards compress individuality into a narrow template of desirability.

Where much of digital art has highlighted innovation and play, these works insist that digital tools are also about discipline, conformity, and control.

Technology as Ideology, Not Just Innovation

The Facetune Portraits expand the conversation about digital art by shifting the focus from what technology can make possible to what it makes inevitable.

Digital tools don’t just generate images—they generate norms.

They quietly shape our bodies, identities, and sense of self.

Everyday software, not just avant-garde technology, has the power to influence culture.

In this sense, the Facetune Portraits open up a parallel history of digital art: one that interrogates the technologies embedded in daily life, not just the spectacular ones celebrated in museums or media.

Why This Matters Today

Digital art is no longer just about creativity or spectacle. It’s about understanding the ideologies embedded in the tools we use every day. By examining software like Facetune, we can see how digital technologies influence not just what we create, but who we are and how we see ourselves.

The conversation expands: it’s not only about what digital art can make, but also what it makes inevitable. And that is a critical shift in how we understand the role of digital art today.

Comments